“We’re just not interested.”

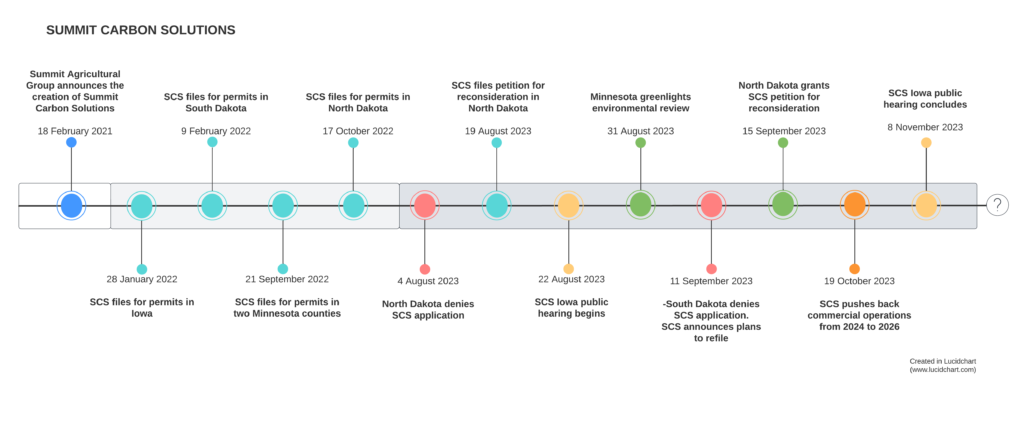

That’s the sentiment that echoes through the testimonies of many landowners at an Iowa Utilities Board public hearing on November 7. The hearing is about Summit Carbon Solutions’ project to build a CO2 pipeline across five states, and the view is summarized in the words of Sue Carter, who owns a farm in the pipeline’s proposed path.

“We feel that it’s not a good idea to sequester the CO2, we feel that it would be detrimental to our farmland, to Iowa, and that we’re just not interested.”

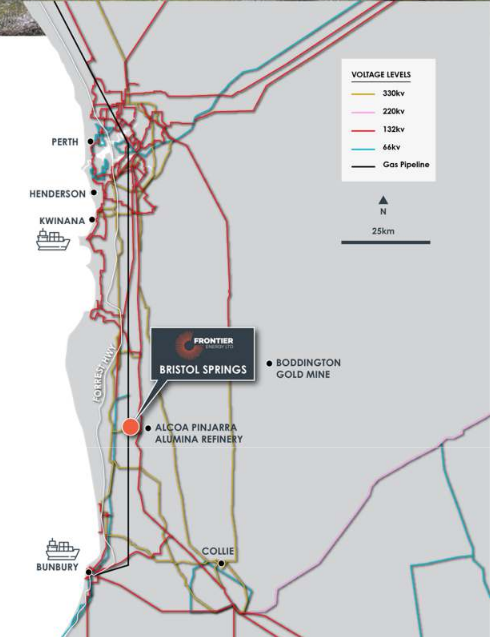

Summit Carbon Solutions, a private company backed by investors such as TPG Rise Climate, Tiger Infrastructure Partners, and John Deere, is planning to build around 2,000 miles of pipeline to transport CO2 captured at 34 ethanol and sustainable aviation fuel plants to geologic sequestration sites in North Dakota. The proposed network spans across Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota.

The project, which would build one of the largest CO2 pipelines in the world, promises to capture and store up to 18 million tons of CO2 per year, offering the Midwest’s ethanol industry a path to net zero.

But building is far from easy.

In September, public service commissions in both North and South Dakota denied key permits to build the pipeline across those states. In Iowa, Summit is encountering staunch opposition from some landowners, who are worried about issues like safety and land preservation, and it is requesting the right of eminent domain over approximately 900 parcels of land.

Commercial operations, which were initially expected for 2024, have been pushed back to 2026, and the project cost has risen from $4.5bn to around $5.5bn.

In a country that, according to some estimates, needs to expand its carbon pipeline network more than ten times in 30 years to reach the ambitious goal of net zero emissions by 2050, Summit’s struggle to advance its Midwest project is emblematic of what might soon happen elsewhere. Navigator CO2 Ventures, for instance, has recently canceled a pipeline project in the area after encountering similar problems.

And the uncertainty around pipeline development might hinder the region’s nascent clean fuels industry, which relies heavily on ethanol production and carbon capture technologies.

*

A potential cost increase was something that Summit took into consideration from the start, “whether that was because of factors related to inflation, supply chain shortages, or a longer-than-expected regulatory process,” according to Sabrina Ahmed Zenor, director of stakeholder engagement and corporate communications at Summit. He pointed out that Summit also increased the project’s expected capacity from 12 million to 18 million tons of CO2 since it was first announced.

Regardless, the way Summit goes about securing success for its project and the extra costs and delays it faces are bound to set an example for developers across the country.

“We need to see one or many of these projects be successful to develop a model as to how to deploy them,” said Matt Fry, senior policy manager at the Great Plains Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting carbon management technologies to achieve climate objectives. “We already have some infrastructure to transport CO2, but we just haven’t seen 1,000 to 2,000 miles transporting 10 plus million tons of CO2 a year yet.”

Already, Navigator has canceled its 1,300-mile Heartland Greenway pipeline, which was supposed to carry CO2 across Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and South Dakota. The company announced the decision on October 20, citing “the unpredictable nature of the regulatory and government processes involved, particularly in South Dakota and Iowa.”

Permitting regulations regarding carbon pipelines change from state to state.

“Some states have deadlines or timelines associated with when an application is submitted to when a decision must be granted, which provides certainty. Some places not so much,” said Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, vice president of government and public affairs at Navigator. “Ultimately, the board did not see a pathway forward that was commercially viable.”

According to Burns-Thompson, Summit’s challenges contributed to the decision as well. Navigator will now focus on a sequestration site in Illinois.

Asked about Navigator’s cancellation, Summit said it “welcomes and is well positioned to add additional plants and communities to our project footprint.”

On a smaller scale, Wolf Carbon Solutions is also planning a 280-mile CO2 pipeline in Iowa and Illinois, where it filed permit applications in February and June respectively. And in May 2022 Tallgrass Energy announced its intention to convert 392 miles of natural gas pipeline into a CO2 pipeline connecting Nebraska, Colorado, and Wyoming.

*

Pipelines have been carrying CO2 in the U.S. for over 50 years, with the first large-scale carrier built in the 1970s. At the moment, there are around 5,000 miles of active CO2 pipelines in the U.S., mostly carrying the gas to oilfields, where it’s used for enhanced oil recovery. For comparison, the country has around two million miles of natural gas distribution mains and pipelines.

“There’s a very high likelihood, almost a certainty, that if the US is to reach net zero by 2050, it’s going to need many hundreds of millions of tons of CCS, maybe a billion,” said Chris Greig a senior research scientist at Princeton University, and one of the lead authors of Net Zero America, a study that presents various pathways for the U.S. to achieve the net-zero emissions goal.

If we capture carbon, we also need to transport it. According to the Net Zero America report, the U.S. would need to develop over 60,000 miles of new CO2 pipelines over the next 30 years, which would come at a capital cost ranging from $170 billion to $230 billion, depending on the overall reliance on carbon capture.

*

The United States is the largest producer of ethanol in the world, and it mostly produces it in the Midwest, with Iowa leading the charge.

Ethanol can be used to make sustainable aviation fuel, and its fermentation process emits a CO2 that is almost pure, making it a very good candidate for carbon capture. The CO2 captured at ethanol plants, in turn, can be used to produce clean fuels such as e-fuels, sustainable aviation fuel, or green methanol.

That means the Midwest is well situated to become a major clean fuel hub, but some say that depends on the successful development of pipelines that can move CO2 at scale.

Pipelines are not the only way to move CO2, which can be trucked or shipped. But Summit’s project is expected to transport around 18 million tons of carbon dioxide annually, and that would require an army of railcars and trucks, and cost much more.

Navigator, whose canceled project was supposed to have the capacity to transport 10 million tonnes of CO2 per year, expandable to 15 million tonnes in the future, estimated that it would have had to employ nearly half a million trucks to move the same amount.

Biofuel maker Gevo has recently vented the possibility of relocating its $1bn Lake Preston Net-Zero-1 sustainable aviation fuel plant if the Summit pipeline doesn’t go through. The Lake Preston project is anticipated to start operations in South Dakota in 2025

“Failure for the Summit pipeline to be built in South Dakota puts our Lake Preston project at severe risk of being relocated to a more advantageous location that has the availability of CCS,” said Kent Hartwig, Gevo’s director of state and local affairs, at a Brown County, South Dakota, commission meeting on October 3.

Because of the cancellation of Navigator’s pipeline, a memorandum of understanding between Infinium and Navigator to produce e-fuels was scrapped. Navigator was supposed to provide Infinium with 600,000 tons of CO2 per year for use as feedstock for e-fuels, an amount of CO2 that would require multiple ethanol emission sources tied together to be delivered. Infinium did not respond to a request for comment.

An alternative could be to produce the fuels in the same place where the CO2 is captured. That’s the business model of CapCO2 Solutions, a company that develops green methanol-producing technology that fits in a shipping crate.

“Ethanol plants are sitting on a gold mine,” said Jeffrey Bonar, CapCO2’s CEO. And that’s regardless of whether large CO2 pipelines get built.

CapCO2 is currently raising money to place its first shipping crate at an ethanol plant in Illinois. Eight to ten shipping crates would be able to process all the carbon captured at an average ethanol plant, making green methanol as a result.

According to experts, though, the scale of carbon capture that pipelines can provide is still needed.

“While it is possible to produce synthetic fuels with CO2, the current scale of these production activities and the markets are not yet able to utilize millions of tons of CO2 per year, so associated CO2 storage would be necessary,” said Fry at the Great Plains Institute. “If we are, as a nation, serious about meeting climate objectives, we’re going to have to figure out how to make this work.”

*

Summit says it has secured voluntary easements for 75%, or around 1,300 miles of the pipeline’s route, and it’s still working to secure rights over all the land it needs. More landowners “are signing every day,” according to Ahmed Zenor, of Summit.

In 2020, a pipeline carrying both CO2 and hydrogen sulfide ruptured in Satartia, Mississippi, sending 45 people to the hospital. The episode was the first major accident involving a CO2 pipeline in at least 20 years — according to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration’s data, there have been 105 incidents since 2003, and no fatalities — and it spurred an ongoing update of PHMSA safety regulations.

Among the landowners who don’t want to give Summit access to their land, the incident exemplifies their safety concerns.

“Pipelines such as the one Summit Carbon Solutions has proposed are highly regulated to ensure public safety,” said Ahmed Zenor in an emailed statement. “In addition to being regulated by the PHMSA, the project is also subject to federal environmental regulations and state oversight.”

Transporting materials via pipeline, she added, is safer than transporting them via truck or rail.

The safety concerns mix with a list of worries, including construction spoiling the land, potential leaks contaminating water sources, misuse of public money, and what some landowners describe as generally aggressive behavior from Summit’s agents trying to convince them to sign voluntary easements.

“They went to nursing homes with donuts to try to convince vulnerable senior landowners,” said Jess Mazour, program coordinator of the Iowa Chapter of the Sierra Club, an environmental organization that’s been active in fighting the pipeline.

Overall, Summit is facing the opposition any linear infrastructure always faces — a Maine transmission line linking hydroelectric dams in Canada to the Northeast, for example, has been slowed down by permitting delays — complicated by a lack of uniform regulations.

“Siting and construction are dealt with on a state-by-state basis for CO2 pipelines,” said Danny Broberg, associate director for the Bipartisan Policy Center’s energy program. “This is not the case for gas pipelines, for which interstate siting and construction authorities exist through FERC, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. One challenge at play for CO2 pipelines is that there is no federal jurisdiction for interstate siting and construction.”

Stakeholders and legislators have started discussing how to overcome the challenge — if, for example, siting and construction for CO2 pipelines should be through FERC or not — and in May, the Biden Administration urged Congress to consider providing federal siting authority for CO2 pipelines as a priority for facilitating clean energy development. No official proposal is on the table yet.

Despite the permitting setbacks, Summit says it believes “the regulatory process around pipeline projects works well.”

*

Eminent domain is, to use the Great Plains Institute’s Fry words, “one of the most contentious things on the planet,” and as activists and opposing landowners have pointed out during the Iowa Utilities Board public hearing, it’s not clear it would apply to CO2 pipelines, at least in Iowa.

“In Iowa, you can only use eminent domain if it’s a public use and convenience,” said Mazour of the Sierra Club. “And that’s one of our biggest arguments. This is not a public benefit.”

Carbon capture, according to Mazour, is extending the life of a harmful industry. “We don’t believe that ethanol is the best solution to take care of our soils and our water and our rural communities and our farmers,” she said. “And then if we have healthy soils and if we treat the land differently and farm differently, we can actually sequester a lot of carbon in our ground.”

A better solution, according to Mazour and the Sierra Club, would be to expand deployment of wind and solar.

Whether Summit is entitled to use eminent domain in Iowa or not is something that will be settled once the Iowa Utilities Board issues its final decision — the public hearing wrapped up on November 8, and there is no deadline they have to meet.

Additionally, Summit has to refile a permit application in South Dakota, and still gain all the necessary permits in North Dakota, Nebraska, and Minnesota.

The debate over eminent domain ties to a more general discussion over the benefits and effectiveness of carbon capture technology. Recently, a Bloomberg investigation found that last year Occidental sold its Century carbon capture facility for way less than it spent building it, after the plant never reached its full capacity in over ten years. The Petra Nova carbon capture facility in Texas has also struggled to meet capacity and financial objectives, and it just recently came back online after suspending operations for over two years.

“Innovation includes risks and some tolerance for failure,” said Broberg at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “It’s going to take the entire toolkit of resources to meet net zero, both from the government and the private sector.”

*

As the Midwest becomes an incubator for plans and strategies to build CO2 pipelines, and conversations are starting over how to make regulations more uniform, developers are probably going to take a few lessons from Summit and Navigator.

The most important of these, according to experts, is how to better engage with communities and spearhead education about carbon capture technologies.

“Everyone’s in a rush to take advantage of subsidies through the IRA,” said Greig at Princeton University. “But you can’t rush communities, right? I’m not convinced that all the developers have the level of sensitive, forward-looking stakeholder engagement and community engagement and discussion that is going to be necessary.”

If government entities are serious about developing carbon capture technologies, however, it can’t just be private companies explaining why we need them, according to Navigator’s Burns-Thompson. “It needs to come from the trusted voice of the regulators themselves. And that’s not just state entities. That’s our federal entities as well.”