The largest carbon capture system in the world is the ocean, sucking in about 31% of CO2 emissions from the atmosphere, which makes it “the world’s greatest ally against climate change.” As a matter of fact, it sucks in so much CO2 that it’s becoming too acidic, endangering its ecosystems along the way.

In the ongoing frenzy to find as many pathways to reverse climate change as possible, scientists and developers are looking to take full advantage of the ocean’s natural carbon sink qualities, while hopefully restoring it to its original, less-acidic state. Direct ocean capture (DOC) removes CO2 from seawater directly, through electrochemical-based methods or calcium looping.

It still hasn’t been deployed on a large scale, but it’s catching the eye of investors, despite not having been blessed by federal subsidies like its sister technology, direct air capture (DAC).

Los Angeles-based Captura, for example, recently announced it has raised over $30m in a Series A funding round from backers like Maersk Growth and Eni Next, while Deep Sky, a Canadian carbon removal developer with partnerships with both Captura and its competitor Equatic, raised CAD 75m ($55.6m) late last year.

Much like direct air capture, DOC holds a big advantage in that there’s plenty of CO2 and seawater to go around, making it, theoretically, endlessly scalable.

But “in many ways, from an engineering standpoint, direct ocean capture seems a better approach to carbon removal, because the medium seawater contains more carbon molecules per unit than air,” David Babson, executive director of the MIT Climate Grand Challenge Initiative, said in an interview. Plus, it can be 100% powered by renewable electricity, whereas direct air capture still requires some heat.

Not that pursuing one denies the other.

“We got into this mess of climate change by taking carbon out from underground and putting it into the air and therefore into the ocean,” Phil De Luna, chief carbon scientist and head of engineering at Deep Sky, said in an interview. “In order to reverse that, we have to take CO2 out of both the air and the ocean and put it back underground.”

Deep Sky, according to De Luna, is “an oil and gas company in reverse,” and much like an oil company, it doesn’t develop its technologies, but rather invests in what’s already been brewing, offering partners money, solutions, and potentially a place to store the CO2 once they have it.

Deep Sky looks for four things when selecting a technology to invest in: it has to be fully electrified and easily scalable, and it has to have low energy intensity and a robust and uncomplicated supply chain. DOC is on its way to tick all those boxes and it should be ready for commercial deployment within a decade, according to Babson and De Luna.

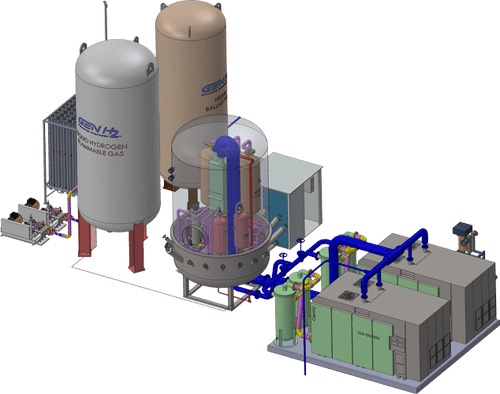

Equatic, one of the companies Deep Sky has partnered with, has two pilot facilities active in Los Angeles and Singapore and is going to announce a larger plant, estimated to remove around 4,000 tons of CO2 per year, in the near future, according to Edward Sanders, Equatic’s chief operating officer.

Its technology is based on modules the size of 20ft shipping containers, which, placed on the coast and powered by renewable energy, pump in large amounts of seawater, pass an electrical current through it, and then trap the extracted CO2 in solid minerals.

The modules are replicable, “like solar cell modules,” according to Sanders, an attractive feature for investors, and the CO2 removal happens within their boundaries, which means you can measure and report how much of it you’ve captured. That’s important for figuring out how many carbon credits to sell – since, as it stands, selling carbon credits is the basis of most of these companies’ revenue models.

As a new technology, DOC is expensive and needs to become cheaper to be deployed at a relevant scale. But unlike direct air capture, it cannot, currently, claim tax credits for carbon sequestration both in the United States and Canada.

The lack of DOC-related subsidies is not an issue for Equatic, which, in addition to removing CO2 from the ocean, also produces around 30 kilograms of green hydrogen per module per day, and is therefore eligible for hydrogen tax credits. Captura, on the other hand, is investing in modules to prove that DOC is, essentially, direct air capture, since “you’re using the surface of the water to capture CO2 from the air, and you’re using this process to remove the CO2 from the water,” according to Babson at MIT.

Captura declined an interview and did not respond to a request for comment.

“It’s certainly one of the flaws in the Inflation Reduction Act that it has constraining language around direct air capture specifically, saying that direct air capture gets the credit and nothing else,” Babson said. “That runs afoul of policy 101. It limits the possibilities.”

The next step is convincing the authorities in charge to include DOC in the technologies eligible for subsidies, which is bound to take some time.

“Unfortunately,” Babson said, “when it comes to climate change and carbon removal and scaling an enormous negative emissions industry, we just don’t have time.”